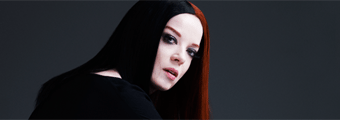

The SPIN Interview: Shirley Manson

Shirley Manson has taken to miming. With her shock of crimson hair pulled into a bun, she declares in a proud brogue, “This is how I used to operate in the world.” She braces against an imaginary wall and shoves, to no avail. “Now, I’m like this.” She slowly pushes the wall six inches, beaming. “Forty-five years old ain’t so bad!”

Though fortitude is a quality most would associate with Garbage’s rebellious redhead, optimism not so much. Her band is about to release their first album in seven years, and Not Your Kind of People picks up from where the alt-’90s brooders left off. Sleaze. Gloom. Glam. Noise. Songs about beloved freaks and lying lovers. Grungy, trip-hop-addled pop designed to stoke the last dance at the end of days. There is one key distinction, however: Garbage are releasing their fifth LP themselves. It’s the most free they’ve felt since solidifying in 1994, when drummer Butch Vig — fresh off producing Nirvana’s Nevermind — and his pals Duke Erikson (guitar, bass, keys) and Steve Marker (guitar, keys), saw a Scottish songbird on MTV with her band Angelfish and knew, instantly, that Manson was their voice.

Manson once told an interviewer that she was afraid of happy people. “I still am,” she says. “Is that willful denial of reality or what?” But the band’s feisty frontwoman, whose most famous declaration is that she’s only happy when it rains, is hardly the misanthrope we remember. She’s begun acting, notably playing a shape-shifting android on Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles, and she lives in Los Angeles, a city famously averse to precipitation. Which begs the question: Is Shirley Manson actually, maybe, just a little bit…happy? She takes a long pause, really mulls it over. “Yeah, I think I’m a happy person.” Then she affects a devilish grin to respond to a query we haven’t yet asked. “And yes, you should be very afraid.”

Well, how does it feel to be with the old band again?

It feels both spectacularly familiar and spectacularly weird. I mean, I never imagined I’d be the age I am and actually have the wherewithal to get my shit together, to pull up out of the mud. When you grind to a halt, to get going again takes a phenomenal amount of effort. To scratch your way up the ladder is hard enough when you’re starting out.

When you’re young, you haven’t been told “no” all that much. It’s easier.

It’s different. When you’re young, you haven’t felt the power of rejection the same way, but you take every “no” a little harder. At this point, I can take a slap or two. Hell, I can take a punch. I’m not as sensitive as I used to be about people not liking me or my band.

Was there any part of you that thought Garbage was over?

I knew we weren’t done. I’m surprised it took us this long to want to make a record again. For me, the spark came when I went to Coachella a couple of years ago. I felt like a lion in a cage. I wanted to chew through my bars. But we’d been the darlings for so long, and then suddenly we weren’t. I remember hearing the White Stripes’ [White Blood Cells] on iTunes in 2001. I clicked on it, heard 30 seconds, and bought it immediately. And then — honest to God — in my head, I was like, “That’s it. You’re fucked.” And I was right.

They were right at the cusp of a pretty big shift.

Them and the Strokes…they were coming from a completely opposite direction, and they blew everything else out of the water. Fair enough, but I knew we’d have to dig really deep to make a record that was going to be relevant in some way. We sounded tired and we were. We had been touring for a decade, living on a bus. We had no idea what was going on in the street, which I think is important for the kind of band we are.

You took up acting in the interim. Did doing something else help you clear your head?

Yeah, it was great to be in a beginner’s mind-set, to not have a clue about the rules, to be scared. On our last tour, in 2005, I would walk onstage and my blood pressure wouldn’t change. I wasn’t excited and that was so sad because it was something I’d loved so much. Inside, I was like, “This isn’t right. You have to stop. You’re going to make bad choices, make bad music.” All of us felt the same way and we just left in the middle of the tour.

You’d also been passed from label to label as the majors shifted and merged. It must’ve felt like you’d lost control of your own destiny.

That, and we signed with an indie because we shared that mentality, but then found ourselves on a massive label overnight [when Almo Sounds was sold to Universal in 2000, placing Garbage on Interscope]. And then you start to hear things from other artists about how the company feels about you. I don’t think the big labels understand that artists have each other’s back, because shit was reaching our ears that we never should’ve heard. The rot set in. We had to get off.

Does any part of you long for the industry of the ’90s — platinum sales, chart positions, big video budgets?

There is not one single shred in my entire body that misses that. And I’ll tell you this also, though I’m sad to say it: To see those fat cunts lose their jobs gave me an unbelievable sense of satisfaction. To know we’ve outlasted them makes me feel so victorious I don’t even know where to start. Because they treat you so well when the money’s pouring in — they’re up your fucking jacksie — but the minute things are not so sweet, you can’t even get them to pick up the phone. Now they’re getting a taste of their own medicine.

Then I don’t need to ask you if it feels good to go it alone?

It does, but it’s also stressful. We’d saved the money we made, put it all into an account because we knew one day we would need it, and it sat there for seven years untouched. We’ve now spent every penny to put this record out, so it’s scary, but that’s art, isn’t it?

What does the album’s title, Not Your Kind of People, mean to you?

It’s a two-fingered salute to people who reject or criticize us. It’s like, “That’s cool. If you’re not into us, fine.” We’re only really interested in people who share our outlook. I mean, that’s our audience, right? The people who fall in love with you musically are the people who connect with what you’re saying and how you say it. Ultimately, it’s about self-acceptance for us. We’re not trying to pretend we’re anything we’re not. We’re not trying to come up with the hippest, coolest sounds on the street. If you like it, come with us. If you don’t, we’re not for you.

What do you think about the idea of your band’s appeal being nostalgic?

I hate nostalgia. I think we’ve made an album that can stand up amongst a lot of records that are being made right now. How other people perceive that is out of our control, and I get that. When I was young, I didn’t necessarily want to listen to anyone over 30. I had no interest in it. There will be tons of young people who don’t want to listen. I totally respect that, but I think there is an audience out there for us if we want it.

You call your fans “darklings.” Where did that come from?

I got to a point where I felt very protective of our fans, felt a kinship with them, and that word resonated. I think it comes from a Robert Browning poem. I have a certain tendency towards the dark that defines me as a singer. I’m not a show-pony girl. I’m not all bright and pink and fluffy. I look at the world with a slight melancholy, always. I think people who are attracted to the band share that. I see death coming and I don’t shirk it.

Where do you think that protectiveness comes from?

It definitely comes from being older. Over the last decade I’ve been struck by how much our music has meant to others. It sounds so hackneyed to say, but it’s true. I used to be very cynical, even embarrassed about it, and now I’m like, “What an amazing privilege to be able to write something that brings somebody comfort or inspires them or changes their way of thinking.” That’s an amazing thing. It’s the best part about being a band.

That darkness you mentioned was a vital part of Garbage. Sometimes you embraced it, sometimes you pushed against it. Has your relationship with that feeling changed?

Seven years on, I’m wiser, more experienced, and way less fearful. I spent so much of my life feeling scared. I don’t know why. I grew up in a nice middle-class family, and nothing majorly traumatic happened to me. But that’s the glorious thing about getting older. The physical deterioration is a little hard to handle, but the fear dissipates and you’re capable of a lot more. Doing the TV show, for instance, I was willing to get up in front of 11 million people and fall flat on my face. I took that risk and it was a pleasant surprise.

Do you think the darkness originated on the schoolyard, in your being bullied as a child?

It was a multitude of things. I was a beacon of attention being the only ginger in the class. People don’t associate red hair, pale skin, and freckles with beauty. Historically, we’ve been persecuted. It’s all animalistic. It’s a weak genetic trait that’s slowly being eradicated from the gene pool. Also, I was a middle child, which I think gives you serious identity issues. And my father was my Sunday school teacher, so it was the perfect storm.

You’ve said the feeling of being an outsider continued into adulthood. You’ve struggled with body dysmorphia. Has any of that gotten better or gone away?

It’s just under the surface. I’m a cutter and I will be for life. The sensation of never feeling good enough or pretty enough will always be there. It’s a constant dialogue, and you just learn to be more powerful than that other voice. When you hear it come up, you shut it down. In terms of fitting in, you know, I don’t have a lot of armor up. I’m a raw nerve and it’s really uncomfortable for a lot of people. There have been so many times where I’m at a dinner party and I’ll say something and you can feel the free fall as silence engulfs the room. It’s not everybody’s way of moving through the world. I need to dial it down a lot.

Garbage was always synonymous with a certain kind of sexy. Is that something you came to embrace over the years?

No, I find it laughable. I was 28 when Garbage broke, so I was old enough to understand the danger in tying your worth to sex appeal. It’s a trap for women because it’s something they can’t hold on to. To me, who you are is the most important thing. What you do says more about your value in the world than how you look. I really believe that, and those are the strengths you can rely on when things get tough, because they inevitably do. That line of thinking stops women from believing in themselves as artists, from being curious and brave. Instead, we wind up with girls that sound ten a penny, who are coming off tour and having their songs handed to them. We’re not hearing authentic experiences from women.

Considering the ’90s, with Garbage, No Doubt, Alanis Morissette, and Courtney Love, did you think things would be different by now?

Yeah, I really felt like my generation burst through the glass ceiling. There were so many alternative female voices being heard in the mainstream, and now it feels like everything is floating back down to how things were prior to the ’60s even, when women dressed pretty and spoke nice and were always putting on like Betty in Mad Men. I want to see some wild, unorthodox thinking; I’m aching for it. I love pop music, and I respect people like Katy Perry and Lady Gaga. They work their asses off and they’ll have the last laugh. But I don’t see any balance out there.

But are we also too critical of women in music? Lana Del Rey, for instance?

It’s unbelievable what’s happened to Lana Del Rey! It’s shocking misogyny. I look at her and say, “What more do you want?” Here’s a beautiful young girl who tried her hand at being a working musician under her own name and it didn’t stick. She had the fortitude to go back to the drawing board and create something new, a perfectly executed re-entry into the world of music, and she’s getting destroyed for the very same thing that Jack White is so brilliant at. Granted, they’re very different artists, but why are we attacking a young girl who’s ballsy and creative? All I can say is they did the same thing to me when I came out. I was constantly being called a phony, and I’m thinking, “I was in a band that failed miserably for ten years. What’s fake about that?” You don’t get in a fucking transit van and tour around Europe if you’re a fucking phony. Let me assure you, it ain’t easy.

You fought the perception that you were just the face of Garbage, even though you wrote songs. What did that feel like, and how did you overcome it?

It was awful. I was finally allowed to be creative, to write and have input into something that people valued, and then I was treated like a piece of flotsam. I wasn’t undervalued; I was dismissed. To say it didn’t sting would be a lie. But I guess there’s a real pugilistic streak in me because I was just like, “Fuck it. I’ll show you,” and I kept at it.

Do you think putting out a solo album would have dispelled that once and for all?

I wanted to put out a solo record because I was stuck on a major label and sick of it. We needed to be Top 5 in the charts and sell at least a million records or Garbage was a failure. [After 2005’s Bleed Like Me] I was like, “This is a mad, nutty game I want no part of.” I wanted to take my ball, go home, and make a very dark, very quiet record that wouldn’t be judged on those terms. I didn’t think for a minute they wouldn’t actually let me release it — that was my own na ï vet é . I’ve told this story and still don’t know if anyone actually believes me, but they said to me, “We see you as the Annie Lennox of your generation.” Now I respect her enormously, but I want to make a record that sounds like me. Their response: “Until you deliver us a pop record, we’re not interested.” It was so extreme that I’m grateful for that kind of rub, because it made me determined to get out of my contract. I realized that I was incorruptible, which is great because sometimes you forget. When a band becomes that successful, you don’t know how much you value that until it’s gone. But I said, “I can live without you. I can live without fame. I can live without success or money and I will be okay. I can make my life exciting for me. Go buy some hooker on 42nd Street because this isn’t for sale.”

So why didn’t you take those songs and put them out on your own?

I have attention deficit disorder. I get bored really quickly. There’s a song I wrote with Grant Lee Buffalo that I’m holding on to. I gave a song to Sky Ferreira, and the nucleus of the new Garbage song “Blood for Poppies” was from those sessions, but I’d kinda moved through that. I want to be really loud now. I’m back to wanting the guitars to roar.

There’s a song on the new album called “I Hate Love,” but that can’t be true.

My dad has taken massive offense to the title of this song. I get a lecture about it almost weekly. Of course, it’s not going up against the concept of true love, but so much is made of love in our society that isn’t real love. Some of my friends who are married treat one another like shit. It’s more to do with the commercialized idea of love and what pain that puts us through. That, and knowing that there will be no more torture in your life than really, truly loving somebody who doesn’t love you back.

Your bandmates have said they hear optimism in your latest lyrics. Do you agree?

Therein lies the dichotomy of me and my band. No, I am a positive person. I’m grateful to be alive. I’m enthusiastic and passionate, but I do see death marching toward me. I see the end of the world. That feeling is omnipresent for me. That was the great part about making this record. When my mom died, I just wanted to quit. If she wasn’t there to hear it, then what was the point? But a good friend of mine said, “That’s the worst thing you could do. Your mom would be the most bummed out by that.” So I recalibrated my relationship with music. I’d never taken myself seriously as an artist. Not as a singer, not as a writer — nothing. I stopped being so hard on myself, and said, “This is what you love, what you’ve done your entire life. Why would you stop now?” I decided to do only what thrilled me, nothing else mattered, and suddenly I was coming from a fearless place. The world wasn’t going to end. The clouds weren’t going to fall. Finally, things were okay.